Chapter Four

"The Man With The Cats"

As I slowly waked up one morning in March, 1970, I heard

a car starting outside and saw that I'd left a light on in the

bathroom and I realized I wasn't at home. I'd spent the night

in the El Rancho Hotel in West Sacramento. With a slightly

uncomfortable feeling I remembered that this wasn't just an

ordinary day. Two biggies--big events or significant bills--

were scheduled. There were 'biggies', 'chickenfeed', 'pork

barrel', and 'bread and butter' (designed to please or appease

your own district) bills. These aren't terms everybody would

use but I did, and certainly most people at the Capitol

understood them.*

The Mountain Lion Bill was up for debate and vote before

the full Assembly, and Alan Sieroty's and my quixotic tax

reform legislation was set to be heard and probably lambasted

by the conservative Rev and Tax Committee. As I threw off the

blanket of sleep, I started feeling the excitement of big

things happening, but another more cautious side of me was

saying, 'pull the covers over your head and hide. Stay in bed,

don't go out there and face those people--your weakness and

hollowness will finally be exposed.' Most people occasionally

feel this basic illogical insecurity--like in the poem my sis-

________________

*Rather than leave you totally to your own extrapolation, I

should add that a 'pork barrel' bill is one which brings

substantial money, employment, or something else of value into

the district you represent. 'Bread and butter' is the same

idea only to a lesser extent and of a more routine nature. In

this day and age a legislator's corporate benefactor may

replace the district as recipient.

ter-in-law B'Ann used to recite:

'You're nothing but a nothing

you're not a thing at all'. . .

'Oh no I'm not I'm just a mouse

that's all I want to be.'*

When I got up and started doing practical things--like

taking a hot shower then a short cold one, and stumbling

around for my razor, the extreme feelings of elation and

apprehension left me. My preoccupation with my feelings

dissipated--it was a real day and I had real work to do.

I'd brought my best suit, freshly cleaned--it was light

blue with slightly darker hairline stripes. You feel good in a

good suit, it integrates with you--it's part of you.

'Hello there kid

You sure look like a brother bat to me'

That's how B'Ann's poem starts.

'Oh no I'm not I'm just a mouse

that's all I want to be.'*

________________

*These semi-nonsensical rhymes were originally used to amuse

our children, but became general family vocabulary.

I knew I wasn't gonna get any votes on account of my

pretty suit, but it was an indirect way of letting my

colleagues know this debate was important to me, and the

possibility of TV coverage made me care about it more than

usual. Janet had picked me a pale blue shirt for the TV camera

and a dark brown tie with an inscription of the seven ages of

man in seven images descending down the tie. The knot was tied

in the shape of a baby's head; at the bottom an old man's head

was represented by just a speck.

Sometimes legislators on the floor will say ridiculous

things just to see whether people are listening or not.

Anyway, as I was saying, Janet had picked me out a brown tie

to go with my shirt.

I put my suit on; thus armored I drove down West Capitol

Avenue, a motel/restaurant/entertainment strip. It's an

extension of the Capitol Mall, but it's across the Sacramento

River in Yolo County. When you hit the Tower--the old

drawbridge leading into Sacramento--there lies the mall,

straight ahead, ten blocks of four-lane boulevard between you

and the Capitol Dome. At first I was thinking about the day's

events and how I'd handle them, and driving slowly, and then

thinking less and less--just wanting to get to my office and

get started, and driving faster and faster on the mall, pass--

ing between new government buildings, heading for the ornate

domed Capitol, ending up zooming down the member's driveway

and stopping abruptly in the underground garage and leaving

the car for one of the attendants to park.

In my office I saw that my desk had the usual pile of

crap on it, and I was about to sit down and go to work, but

there was a sheet of typewriter paper on the seat of my chair

with:

ATTN: MR. D.

written on it in large red letters. Typed under the letters

was:

Sign declaration of candidacy. Form

attached. I have to deliver to Sec.

of State's office today.

--Wanda

Oh shit, I thought, I've got to run for office again this year--

that's a hell of a thing to have to think about now. It seemed like I

was always recovering from one election or getting ready for

another. Assembly terms were only two years. '66-8, '68-70, '70-???

up on the carousel again? I signed the form and took it into

the outer office and stuck it under the carriage bar on

Wanda's typewriter. She put things on my chair, because she

knew I was going to sit there; I put things in her typewriter

--she couldn't type and I couldn't sit, without first

attending to each others' special errands.

I'd originally hired Wanda as my second secretary on the

recommendation of a friend at Solano College in my district.

Dorothy Loviach was now working for the Assembly Criminal

Justice Committee. The powers-that-be usually liked us to hire

from the Capitol secretarial pool but after two phonecalls and

one interview they let me bring her to Sacramento, warning me

she'd probably be somewhat immature. The only thing I noticed

was that she had a little trouble admitting she didn't know

something, at first, but she got over that fast and in a

year's time had learned so much she became my First Secretary-

-at age 19--the youngest at the Capitol.

Hiring Wanda had seemed something I 'ought to' do--'I

should try this'--partly because she seemed right and partly

because my friend at Solano College would think well of me for

doing it. In the end it showed me to have become a good

Capitol teacher and her a good learner, fast and thorough. We

were a good boss/secretary team.

A male chauvenist puts males above females, thinks women

exist for men--that's the extreme, of course, and though I

didn't really believe this, I was, momentarily, unhappy and a

little angry when, two years later, Wanda got married and moved to

Glendale. I knew better, but felt a little like my male perogative had

been usurped. Like a good boy I went to the wedding, which was dull.

Wanda was sharp and outstanding but her family and friends

didn't live up to my expectations. I think she planned and

paid for her own wedding--maybe I'm just imagining that to

have been the case--I don't really remember.

Though I was unhappy when Wanda moved to Glendale, that

ain't nothin' compared to when I learned that she'd gone to

work there for an arch-conservative Republican Assemblyman,

Mike Antonovich. I hadn't trained her for that. Later, she

visited me and said she'd quit the job because it wasn't

challenging enough.

Back at my desk I settled down to reading some memos from

staff, and scribbling reactions on some of them--like:

Yeah.

or: Sure, Go.

Do it.

or: No, that's not right

or: We've got to find this out first.

Wanda had also left notes about people I should call, but it

was 7:30, too early for phonecalls. Even when biggies are

scheduled, routine doesn't stop--luckily there was still time

to cover some of the details on my desk. I was glad I was

alone. I could do this stuff better when nobody was around to

bug me. Pretty soon there'd be student interns at a table at

one end of my office, two secretaries in the outer office, and

Mike Gage, my legislative assistant, walking back and forth

between all of us. And by nine o'clock the phones would be

ringing, sometimes almost constantly.

I'd just dictated a memorandum when Wanda opened the door

from her office to mine. As she saw me she said, "I like your

suit."

I smiled and said thanks.

"I saw my typewriter--I'll take the papers down before we

get too busy--see you in a few minutes."

When Wanda got back, we went to work. We had an intercom

system but usually it was easier to just leave the doors open

and raise our voices a little when we had to communicate.

Gage finally dragged his ass in about ten after nine.

Don't misunderstand me. Mike worked hard and long hours but he

sort of made a statement of independence by not hewing to

routine scheduled hours. Mike was 24 with red hair which was

slightly balding. He was almost always dieting, though he was

only a little overweight, and he was always quitting smoking.

Mike was a very hard worker and politically brilliant. The

Mountain Lion Bill was partially Mike's baby and he started

bugging me about it immediatly. "Okay, John, the Mountain Lion

bill's today," (like he's telling me something I don't know,)

"and I'll bet you haven't talked to Zberg and Sieroty."

"I'm going to do that on the floor--"

"How many Aye votes have you got counted?"

"I haven't got a vote count, I don't think we need one--I

think we're in."

"You could still muff it on the floor. You won't have any

lions backing you up down there this time."

"You mean you didn't get them again?" (For a press

conference earlier in the year I'd been flanked by two live

lions.) "I'd expected to take them to the floor with me."

"To help you lion up votes."

"Yeah," I said, as the corners of both our mouths turned

up in shit-eating grins. (or more politely, "sardonic", "compulsive"

"self-approving"...grins)

The tension of the job made clowning inevitable. Probably

the craziest group of clowns and the best staff I ever had was

in 1974 when I was campaigning for the State Senate. Mike Gage

was my campaign manager and Edna Brown and John Harrington

were my legislative assistants. Gage and I and Harrington had

a habit of startling each other by picking up a piece of

furniture and throwing it across the room, intending that it

should be caught, which it usually was. We threw only light

chairs and small end tables. Gage might come into my office

and stand looking down at some material on an intern's desk,

then suddenly turn and grab a chair and toss it to me where I

stood by my desk. Not wanting to be outdone, I'd call for Harr

--ington and throw it to him as he came through the doorway.

John managed to catch the chair and ground it, cursing at us.

Once John and I tossed large ashtrays to each other at

the same time, and the two ashtrays hit in mid-air, showering

glass all over. We were greatly surprised. Ruth Siegle, one of

my district representatives, once gave me a metal horn with a

rubber squeeze ball on the end of it--sort of a Harpo Marx

device. At times of frustration and bedevilment I used to blow

it--sometimes into the telephone.

Edna Brown joined my staff after working a year and a

half free as an intern. She was a great lady.

By 9:30 both interns and my second secretary had arri-

ved on the scene. The first intern had been dispatched for

coffee. Somehow we all managed to touch base, say hello, and

get on with the various things we were doing in between

phonecalls, reading memos, and opening the day's mail.

When I left the office to go to the legislative chambers

a little after ten, Wanda gave me a folder with legitimate

mail in it, junk having been sorted out. I might have time to

read it during dull moments on the floor.

Session was supposed to start at ten sharp, but never

really got underway until about 10:30. This demonstrated yet

another 'pair of opposites', the Virtue of Promptness but the

Sagacity of Tardiness. You waste time by being on time,

because others generally aren't. Today I was prompt because,

as I'd promised Gage, I needed to try to line up at least a

few votes before debate. I hadn't done a detailed job of

getting advance commitment. The opposition came from limited

quarters. We seemed to have a popular thing going.

The back entrance to the Assembly Chambers (For

Legislators Only) is a narrow hallway within which the

members' elevator stops. Coming out of the elevator I walked

quickly past the Sergeant-at-Arms, saying hello almost over my

shoulder. Anyone who wasn't a member would've been stopped at

that pont. Entering the chamber I walked under the Speaker's

rostrum and 80 feet across the floor to my desk, noticing a

couple of other early arrivals on my way. After putting down

my files I made a beeline for my former seatmate, Ernie

Mobley. I told Ernie my Mountain Lion Bill was coming up today

and I hoped I could count on his vote. He told me that his

farmers and cattlemen didn't like the bill. "It just concerns

sports shooting," I told him, "livestock is still protected."

He said he'd listen to the debate and make up his mind. I had

similar conversations with eight or ten others, catching them

near the door as they trickled in. Some, I asked for their

vote out and out. "Are you familiar with AB 660, my Mountain

Lion bill?" etc. Others, I knew what their hesitations might

be so that's where I started out talking. At least half of

those I talked to were favorable about the bill.

Just a little before a quorum arrived on the floor I went

to the coffee room in the back of the Assembly Chamber to sip

coffee and see if I could pick up a couple more votes. Willie

Brown was in a corner talking to a member of his staff. I

mentioned the bill to him briefly but already knew I had his

support on it. Willie had a copy of the little book Jonathan

Livingston Seagull in his hand. He said he was intrigued with

its message. "Birds and man have no limits", he said.

Coffee and donuts are provided in this rear chamber for

legislators and their guests. A P.A. system relays the

activities of the house, so you can talk to peole, hear what's

going on out on the floor, and drink coffee at the same time.

It's a formality that's persisted, that food and beverage

aren't allowed out on the floor. From the coffee room you can

be back on the floor in a matter of seconds, voting or in the

middle of debate...I got up, leaving my half empty coffee cup,

and started to walk toward the swinging door into the chamber.

Before I reached it, it opened and my good friend Assemblyman

Alan Sieroty came in. He smiled as if he was actually glad to

see me and said, "I was lookng for you--my staff tells me

you're going to take up your Mountain Lion bill today--

anything I can do to help?"

"I was going to ask you if you would--just listen to

debate and jump in if you think I'm in trouble. You know the

bill."

"Sure. It's a good bill. I wish I had a bill with a real

live animal in it."

"Your paleontologist friends couldn't provide you with

one, could they?" I said. Alan had recently, on request of

some friends of his from academia, put in a bill to designate

Smiladon Californicus (the California Sabretooth Tiger) the

'Official State Fossil'.

"No," Alan responded, "but I sure would've liked to bring

one up here for debate."

"Do you think it'd fit in the elevator?"

"I think so. I don't think they're that big."

"I can see it--on the way up from the basement you and

Curly" (the elevator operator) "each holding a tusk."

Most legislators are so embroiled in their own bills that

they don't have time to think of volunteering to help somebody

else. Alan had a lot of his own going on but he often knew of

my important bills, because we shared interests. And, we were

just darn good friends.

At 10:30 a quorum (majority of the members) having

appeared, the House was called to order and we started taking

up the day's business item by item in the order designated in

the pamphlet (daily file) on our desks. While the Speaker (or

his designated helper) went through routine matters in a

perfunctory mumbo-jumbo manner, I sat half-listening but going

through the material in the Mountain Lion file to prepare my

opening statement. I already knew the material A to Z--I just

had to make a couple decisions about where to begin my speech.

Assembly rules provide that the bill's author has an

opening and a closing statement, a maximum of five minutes for

each. Other speakers are similarly limited. The presence of

active opposition meant to me I should give the bill full

treatment. Others following in debate are recognized to speak

in the order in which they raise up their microphones--the

mikes are mounted on flexible metal arms and can be stuck up

in plain sight...sort of like a kid raising his hand in

school.

At 10:55 we reached item 22 on the Daily File. The Clerk

read the bill number, AB 660. I raised my mike and the Speaker

recognized me, saying, "Mr. Dunlap, are you ready to proceed?"

I answered, "Yes, Mr. Speaker," and looking around saw two

other members raise their mikes--the opposition was prepared,

not lying in the weeds or forgetting their job.

I began my speech.

"Members--in 1923, a year after I was born, there were

two passenger pigeons in the whole world--both were males.

Rather obviously, there aren't any passenger pigeons now. We

have now about forty California Condors alive,* and their

________________

*Since then the number went down to about a dozen and

Zoologists have now started capturing eggs and raising baby

Condors in captivity, with the idea of replanting them in the

wilds. Their number now is again in the forties.

number has been diminishing. Maybe they'll survive and maybe

they won't...Too many times, we've recognized that a species

is endangered--too late. This hasn't just happened, we made it

happen." I went on with the guilt approach, not just to try to

make them feel miserable, but to get them to recognize that

the Mountain Lion Bill gave us a chance to do the right

thing, start turning around and taking responsibility for our

actions.

I continued, "The State used to pay people to shoot

mountain lions--this bill is the next logical step after

removal of the bounty--the opposition may have said things to

you about the bill, but what it really does is quite simple.

It prohibits sport shooting of the California Mountain Lion.

That's all. No more no less. AB 660 has the support of all

major conservation organizations including the Audubon Society

and the Sierra Club--also, the Vallejo Rod and Gun Club, and

the Mountain Lion Coalition."

Gage and I were in on the formation of the Mountain Lion

Coalition, along with several wildlife preservationists and

scientists. The group was formed to help enlist support and

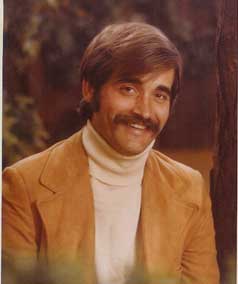

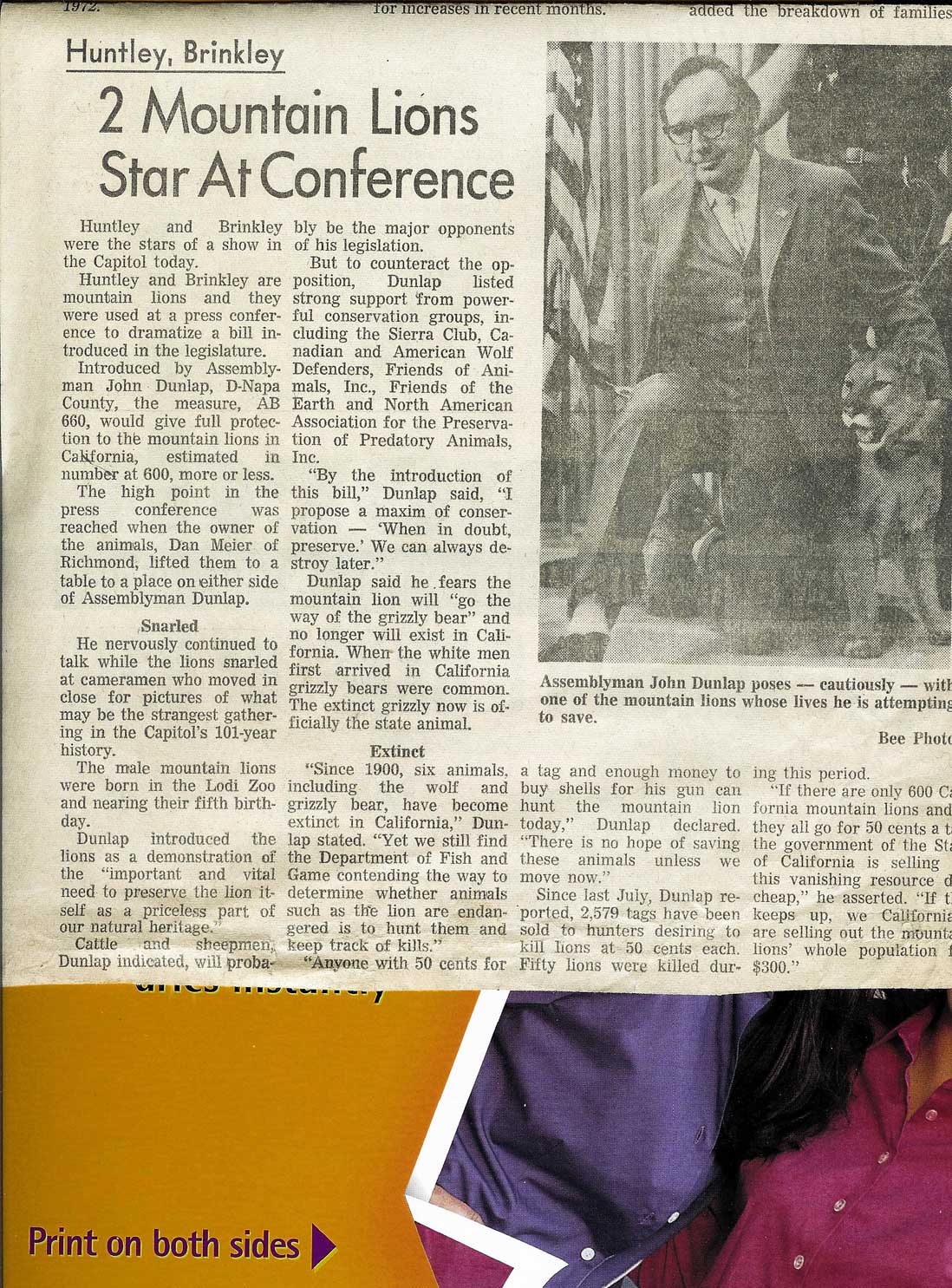

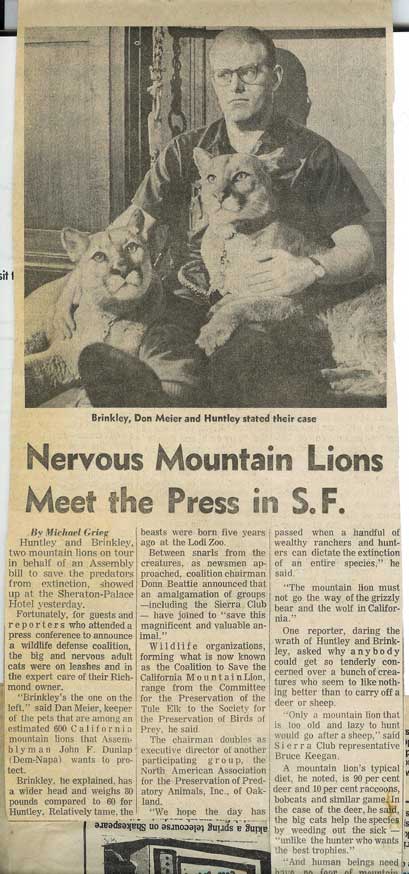

develop publicity. At one strategy session a coalition member

brought tame mountain lions with him. Mike, attending for me,

had a brainstorm and asked if the lions could be used at a

press conference, to give the bill a good sendoff. The owner

consented, but when Mike told me about it I was at first very

negative. It seemed like unnecessary grandstanding.

Mike said, "You know darn well it'll help the bill--it'll help make

people less afraid of lions and it'll increase the number of

people that read about your press conference by 5,000 percent.

Drop your false modesty, John." Mike kept on arguing, and I

finally gave in, partly to him and partly to my ego, which

said 'Go Man Go.' I said to myself, 'I can use the press

conference to emphasize the importance of the bill as a symbol

of the need for conservation of all wildlife'--this satisfied

my image of myself as 'a thoughtul person who doesn't just go

off grandstanding'.

The lions arrived at the Capitol through the members'

entrance in the underground garage and were taken out of the

car in their cage, which was wheeled over to the Assembly

members' elevator, which took them to the first floor. Curly

for years after that used to refer to me as 'the man with the

cats'. They were taken to a small room between the governor's

office and the press conference room. This is where I met

them, about thirty seconds before the conference started. I

hadn't thought to be apprehensive, but I became so instantly

when I went in there and first saw them. They were big, bigger

tha St. Bernards and a lot more agile, and they were moving

around out of the cage. I was glad to see the owner had them

on leash. I was only a little scared. I said, "Well, it's time

to get started, will you bring them in?" And we went into the

press conference room.

The owner brought the lions up and stationed them one on

each side of me at the conference room table. Before I even

sat down the TV cameras started to click and spin. I smiled

out at them, as if to say, "My lions and I have got a great

bill; we want you to listen and help tell our story to the

world." I launched into my presentation, introducing the lions

and the bill. I pretty well lost myself in the show, and

responding to questions afterward--except once when the lion

to my left was moving around and straining at his collar. I

patted his front paw to try to quiet the beast, and it

responded with halfway between a snarl and a roar and reared

its head. I felt uneasy, bordering a little on panic. What the

hell do I do now?--it wouldn't look good if I left--not at

all--but the owner calmed it down right away--later, he told

me its paws were sensitive because they'd been surgically

declawed.

Once John and I tossed large ashtrays to each other at

the same time, and the two ashtrays hit in mid-air, showering

glass all over. We were greatly surprised. Ruth Siegle, one of

my district representatives, once gave me a metal horn with a

rubber squeeze ball on the end of it--sort of a Harpo Marx

device. At times of frustration and bedevilment I used to blow

it--sometimes into the telephone.

Edna Brown joined my staff after working a year and a

half free as an intern. She was a great lady.

By 9:30 both interns and my second secretary had arri-

ved on the scene. The first intern had been dispatched for

coffee. Somehow we all managed to touch base, say hello, and

get on with the various things we were doing in between

phonecalls, reading memos, and opening the day's mail.

When I left the office to go to the legislative chambers

a little after ten, Wanda gave me a folder with legitimate

mail in it, junk having been sorted out. I might have time to

read it during dull moments on the floor.

Session was supposed to start at ten sharp, but never

really got underway until about 10:30. This demonstrated yet

another 'pair of opposites', the Virtue of Promptness but the

Sagacity of Tardiness. You waste time by being on time,

because others generally aren't. Today I was prompt because,

as I'd promised Gage, I needed to try to line up at least a

few votes before debate. I hadn't done a detailed job of

getting advance commitment. The opposition came from limited

quarters. We seemed to have a popular thing going.

The back entrance to the Assembly Chambers (For

Legislators Only) is a narrow hallway within which the

members' elevator stops. Coming out of the elevator I walked

quickly past the Sergeant-at-Arms, saying hello almost over my

shoulder. Anyone who wasn't a member would've been stopped at

that pont. Entering the chamber I walked under the Speaker's

rostrum and 80 feet across the floor to my desk, noticing a

couple of other early arrivals on my way. After putting down

my files I made a beeline for my former seatmate, Ernie

Mobley. I told Ernie my Mountain Lion Bill was coming up today

and I hoped I could count on his vote. He told me that his

farmers and cattlemen didn't like the bill. "It just concerns

sports shooting," I told him, "livestock is still protected."

He said he'd listen to the debate and make up his mind. I had

similar conversations with eight or ten others, catching them

near the door as they trickled in. Some, I asked for their

vote out and out. "Are you familiar with AB 660, my Mountain

Lion bill?" etc. Others, I knew what their hesitations might

be so that's where I started out talking. At least half of

those I talked to were favorable about the bill.

Just a little before a quorum arrived on the floor I went

to the coffee room in the back of the Assembly Chamber to sip

coffee and see if I could pick up a couple more votes. Willie

Brown was in a corner talking to a member of his staff. I

mentioned the bill to him briefly but already knew I had his

support on it. Willie had a copy of the little book Jonathan

Livingston Seagull in his hand. He said he was intrigued with

its message. "Birds and man have no limits", he said.

Coffee and donuts are provided in this rear chamber for

legislators and their guests. A P.A. system relays the

activities of the house, so you can talk to peole, hear what's

going on out on the floor, and drink coffee at the same time.

It's a formality that's persisted, that food and beverage

aren't allowed out on the floor. From the coffee room you can

be back on the floor in a matter of seconds, voting or in the

middle of debate...I got up, leaving my half empty coffee cup,

and started to walk toward the swinging door into the chamber.

Before I reached it, it opened and my good friend Assemblyman

Alan Sieroty came in. He smiled as if he was actually glad to

see me and said, "I was lookng for you--my staff tells me

you're going to take up your Mountain Lion bill today--

anything I can do to help?"

"I was going to ask you if you would--just listen to

debate and jump in if you think I'm in trouble. You know the

bill."

"Sure. It's a good bill. I wish I had a bill with a real

live animal in it."

"Your paleontologist friends couldn't provide you with

one, could they?" I said. Alan had recently, on request of

some friends of his from academia, put in a bill to designate

Smiladon Californicus (the California Sabretooth Tiger) the

'Official State Fossil'.

"No," Alan responded, "but I sure would've liked to bring

one up here for debate."

"Do you think it'd fit in the elevator?"

"I think so. I don't think they're that big."

"I can see it--on the way up from the basement you and

Curly" (the elevator operator) "each holding a tusk."

Most legislators are so embroiled in their own bills that

they don't have time to think of volunteering to help somebody

else. Alan had a lot of his own going on but he often knew of

my important bills, because we shared interests. And, we were

just darn good friends.

At 10:30 a quorum (majority of the members) having

appeared, the House was called to order and we started taking

up the day's business item by item in the order designated in

the pamphlet (daily file) on our desks. While the Speaker (or

his designated helper) went through routine matters in a

perfunctory mumbo-jumbo manner, I sat half-listening but going

through the material in the Mountain Lion file to prepare my

opening statement. I already knew the material A to Z--I just

had to make a couple decisions about where to begin my speech.

Assembly rules provide that the bill's author has an

opening and a closing statement, a maximum of five minutes for

each. Other speakers are similarly limited. The presence of

active opposition meant to me I should give the bill full

treatment. Others following in debate are recognized to speak

in the order in which they raise up their microphones--the

mikes are mounted on flexible metal arms and can be stuck up

in plain sight...sort of like a kid raising his hand in

school.

At 10:55 we reached item 22 on the Daily File. The Clerk

read the bill number, AB 660. I raised my mike and the Speaker

recognized me, saying, "Mr. Dunlap, are you ready to proceed?"

I answered, "Yes, Mr. Speaker," and looking around saw two

other members raise their mikes--the opposition was prepared,

not lying in the weeds or forgetting their job.

I began my speech.

"Members--in 1923, a year after I was born, there were

two passenger pigeons in the whole world--both were males.

Rather obviously, there aren't any passenger pigeons now. We

have now about forty California Condors alive,* and their

________________

*Since then the number went down to about a dozen and

Zoologists have now started capturing eggs and raising baby

Condors in captivity, with the idea of replanting them in the

wilds. Their number now is again in the forties.

number has been diminishing. Maybe they'll survive and maybe

they won't...Too many times, we've recognized that a species

is endangered--too late. This hasn't just happened, we made it

happen." I went on with the guilt approach, not just to try to

make them feel miserable, but to get them to recognize that

the Mountain Lion Bill gave us a chance to do the right

thing, start turning around and taking responsibility for our

actions.

I continued, "The State used to pay people to shoot

mountain lions--this bill is the next logical step after

removal of the bounty--the opposition may have said things to

you about the bill, but what it really does is quite simple.

It prohibits sport shooting of the California Mountain Lion.

That's all. No more no less. AB 660 has the support of all

major conservation organizations including the Audubon Society

and the Sierra Club--also, the Vallejo Rod and Gun Club, and

the Mountain Lion Coalition."

Gage and I were in on the formation of the Mountain Lion

Coalition, along with several wildlife preservationists and

scientists. The group was formed to help enlist support and

develop publicity. At one strategy session a coalition member

brought tame mountain lions with him. Mike, attending for me,

had a brainstorm and asked if the lions could be used at a

press conference, to give the bill a good sendoff. The owner

consented, but when Mike told me about it I was at first very

negative. It seemed like unnecessary grandstanding.

Mike said, "You know darn well it'll help the bill--it'll help make

people less afraid of lions and it'll increase the number of

people that read about your press conference by 5,000 percent.

Drop your false modesty, John." Mike kept on arguing, and I

finally gave in, partly to him and partly to my ego, which

said 'Go Man Go.' I said to myself, 'I can use the press

conference to emphasize the importance of the bill as a symbol

of the need for conservation of all wildlife'--this satisfied

my image of myself as 'a thoughtul person who doesn't just go

off grandstanding'.

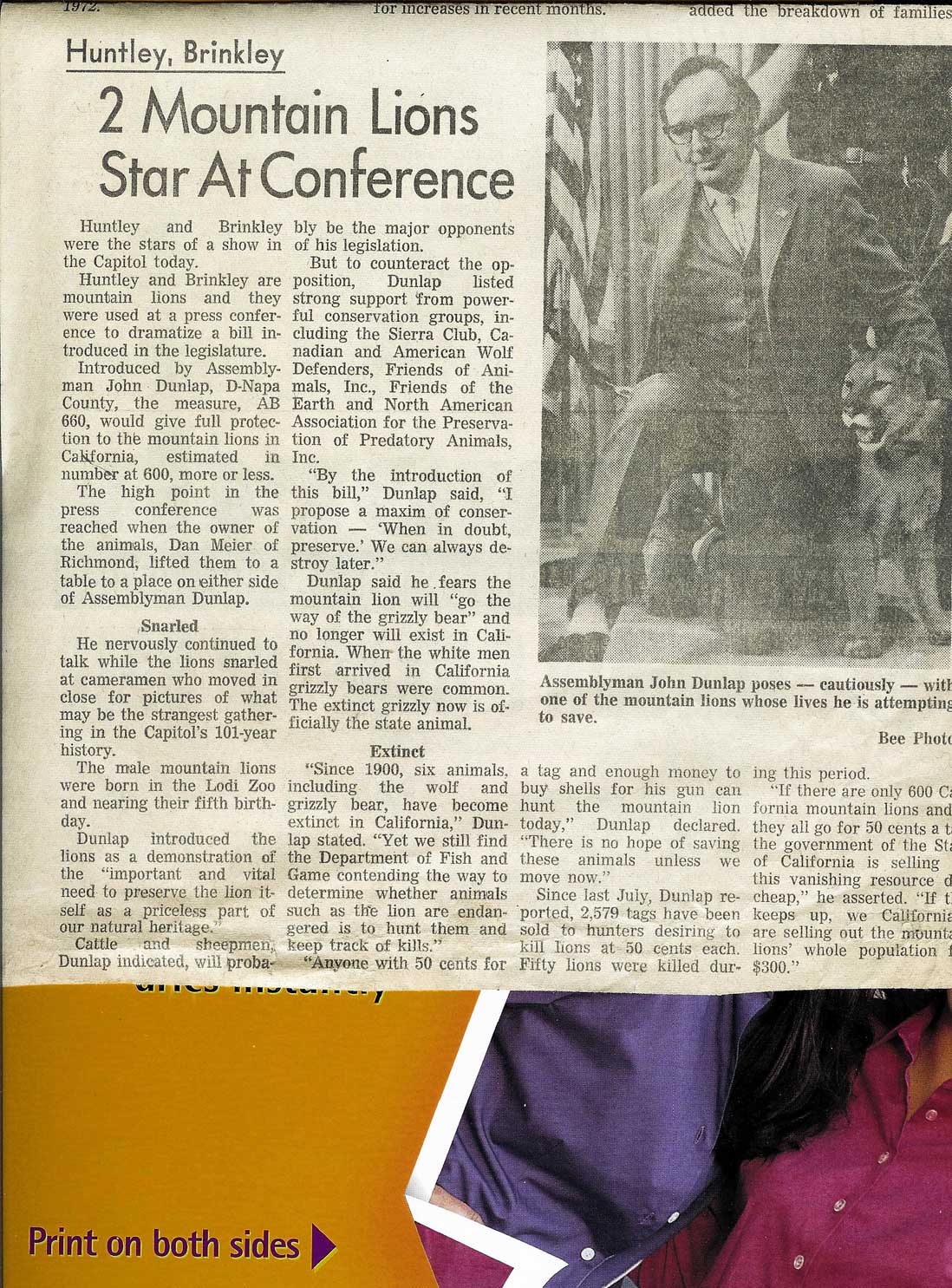

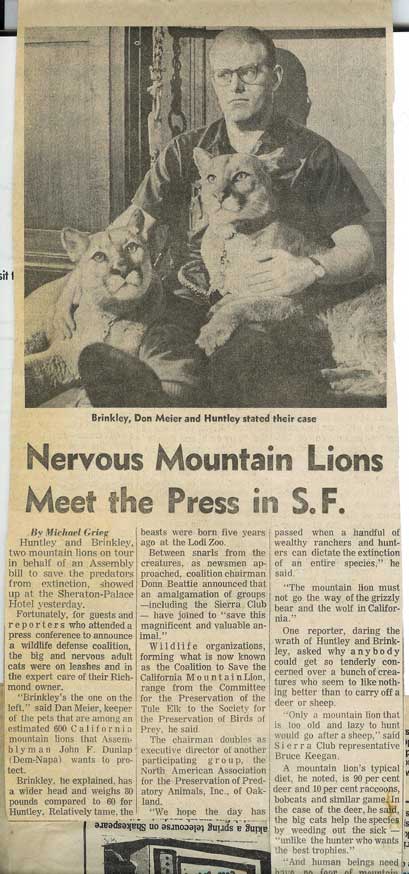

The lions arrived at the Capitol through the members'

entrance in the underground garage and were taken out of the

car in their cage, which was wheeled over to the Assembly

members' elevator, which took them to the first floor. Curly

for years after that used to refer to me as 'the man with the

cats'. They were taken to a small room between the governor's

office and the press conference room. This is where I met

them, about thirty seconds before the conference started. I

hadn't thought to be apprehensive, but I became so instantly

when I went in there and first saw them. They were big, bigger

tha St. Bernards and a lot more agile, and they were moving

around out of the cage. I was glad to see the owner had them

on leash. I was only a little scared. I said, "Well, it's time

to get started, will you bring them in?" And we went into the

press conference room.

The owner brought the lions up and stationed them one on

each side of me at the conference room table. Before I even

sat down the TV cameras started to click and spin. I smiled

out at them, as if to say, "My lions and I have got a great

bill; we want you to listen and help tell our story to the

world." I launched into my presentation, introducing the lions

and the bill. I pretty well lost myself in the show, and

responding to questions afterward--except once when the lion

to my left was moving around and straining at his collar. I

patted his front paw to try to quiet the beast, and it

responded with halfway between a snarl and a roar and reared

its head. I felt uneasy, bordering a little on panic. What the

hell do I do now?--it wouldn't look good if I left--not at

all--but the owner calmed it down right away--later, he told

me its paws were sensitive because they'd been surgically

declawed.

The conference was a success; we had a front page photo

on 18 California daily newspapers, plus the London Daily Mail

(for whatever that was worth). The only negative came in a

letter from a Vallejo constituent, who said, "O.K., Dunlap,

have you forgotten about us Senior Citizens? You're so busy

with the goddamn Mountain Lion--have you forgotten about

Property Tax Relief? Is the lion more important than taking

care of the people?" This guy didn't give a hoot for the

mountain lion. As far as he was concerned, conservation was

strictly a luxury--and talking to him about the mountain lion

was like talking Capitalism versus Communism to somebody who

doesn't have enough to eat. Of course there were people out

there who'd use anything against me they could (and maybe he

was one of them)--people glad to have a chance to say, 'there

goes Dunlap again, off on a tangent that has no bearing on anything'.

The conference was a success; we had a front page photo

on 18 California daily newspapers, plus the London Daily Mail

(for whatever that was worth). The only negative came in a

letter from a Vallejo constituent, who said, "O.K., Dunlap,

have you forgotten about us Senior Citizens? You're so busy

with the goddamn Mountain Lion--have you forgotten about

Property Tax Relief? Is the lion more important than taking

care of the people?" This guy didn't give a hoot for the

mountain lion. As far as he was concerned, conservation was

strictly a luxury--and talking to him about the mountain lion

was like talking Capitalism versus Communism to somebody who

doesn't have enough to eat. Of course there were people out

there who'd use anything against me they could (and maybe he

was one of them)--people glad to have a chance to say, 'there

goes Dunlap again, off on a tangent that has no bearing on anything'.

I continued with my floor presentation, "The mountain

lion is an endangered species because, by our continued

population expansion and exploitation of natural resources,

we've taken away part of the lion's homeland. On top of this,

we're shooting the lions for sport. No one bill can reverse

the process of destruction of the lion's natural habitat, but

by this bill alone, we can stop sport shooting.

"The opposition would have you believe the mountain lion

is a marauder of livestock and ravager of children.* This is

absolutely untrue--we aren't talking about the lions they

threw Christians to at the Circus Maximus in ancient Rome.

Mountain lions are shy animals who avoid contact with humans--

the deer hunter who suggested this bill to me had seen a lion

twice, for a few seconds each time, in thirty years of deer

hunting. Lions are carniverous but they feed on other wild

animals, principally deer--and, an adequate number of lions

helps keep the deer population within the natural limits of

its feed supply. Overpopulation of deer can cause the herd to

become sickly and actually threaten its existence. This is why

some thoughtful hunters support my bill."

________________

* Since the time of my bill, a young woman jogging in the Yosemite area

was killed by a Mountain Lion. This tragically illustrates that

the worst can happen. However, since that time Moutain Lion

protection survived an initiative vote of the people which

sought to eliminate it.

I went on to say that, occasionally, an old and decrepit

or wounded lion may kill a few sheep--but I pointed out that

the bill has a safeguard built into it for just such lions--

when a lion has been killing any domestic animals, the fish

and game department may issue a special permit to kill that

lion. I continued speaking, "The most often quoted survey says there

are 600 lions in the State--and diminishing. But, in fact, we don't know

how many there are--even if you believe I'm a little wrong and

there are twice as many as this estimate, it's far better not

to take a chance--we didn't act in time to save the pigeons

but it's not too late for the lions. A principle of

conservation should be, When in Doubt, Preserve. If we find

there are more lions than we thought, we can always start

killing them again."

At this point my time was almost up and I sensed that my

message was getting across, but that I'd soon lose attention

from the members that were listening--and I was pleased to see

that many were. It was time to close.

"This bill isn't," I began, thinking of the letter from

my Vallejo constituent, "just for the benefit of the posey

pluckers or the very few wildlife enthusiasts who'll have a

chance to see a lion. We are saving lions because they're part

of the natural ecosystem on which we all depend. If we got rid

of all the lions we'd probably survive--the likelihood of the

destruction of this one species so upsetting the cycle of the

ecosystem as to destroy it, is remote--but if we don't learn

to stop with the lion, when are we gonna learn? Maybe only

when it's too late for us as well as the passenger pigeons.

The fate of man on earth rests, in part, on how well we learn

to respect the needs of other living things." I sat down,

looking in the direction of Alan Sieroty's seat. He gave me a

nod and silently clapped his hands, indicating approval. This

was what I was looking for.

My opening presentation had taken almost the full five

minutes. On some bills the opposition doesn't feel strongly

enough about it to take it on openly on the floor. When this

occurs, it's best to undersell the bill--not make much of a

speech, because your own rhetoric may spark your foes into

action. On an occasional bill you may even try to 'mumble it

through'. This may involve using one, two, or a maximum of

three sentences which describe what the bill does but skirt

its potential controversy. If I'd tried to 'mumble through'

the Mountain Lion bill, I'd have said something like, "Mr.

Speaker and members, this bill relates to fish and game

provisions protecting various species of mammals. It was

amended in the Assembly Natural Resources Committee to clarify

and strengthen its provisions. I ask for an aye vote." Then

I'd flip my voting switch to green and sit down and start

reading a book or talking to my neighbor, acting nonchalant.

Meanwhile somebody jumps up saying, "Hey hey hey he's trying

to mumble it through but so and so and so are opposed to it--

he lies!" Or, "Mr. Speaker, Mr. Speaker, Assemblyman Dunlap

has just tried to mumble through a bill that took five hours

of committee time in two separate hearings. There were at

least five opposition witnesses and the whole agricultural

community is opposed...It's an insult to the intelligence of

this great debating body."

But I had given the bill full treatment, and though I

expected to carry it without much difficulty, I knew there'd

be some debate. While the opposition started up I checked over

my notes to see if I missed anything.

"Does Mr. Dunlap know," a conservative Democrat was

speaking testily, "that there are over 3000 mountain lions

roaming the hills of California?" He went on to proclaim that

my bill was a forerunner of the extreme preservationist

philosophy and if successful would be followed by bills to

prohibit shooting coyotes, bobcats, and sooner or later even

rattlesnakes. He also suggested that once these bills were

through I'd probably introduce one to outlaw hunting rifles,

since they'd no longer be necessary.

I figured he'd claimed too much and wouldn't be taken

seriously by many; he'd also exposed his affinity to the

National Rifle Association. But to be on the safe side I made

a couple of notes to respond in my closing statement.

Next, a Republican got to this feet and recited the

organizations opposed to my bill: Farm Bureau, Cattleman's

Association, National Rifle Association, etc. He charged that

the lions in the Sierra foothills were even now marauding

sheep and cattle and if livestock owners couldn't protect

their property the price of meat would rise even higher than

it already was. He went on to inform us that a renowned

university zoology professor had testified in committee that

my bill was unnecessary. I made notes again, as my friend Ed

Zberg put up his mike and was recognized.

Ed said that it was probably unnecessary for him to speak

but he just wanted everybody to know that this was a carefully

thought-out bill, well-drafted and thoroughly heard in

committee--that the testimony in committee was in conflict as

to how many lions there were but the most reliable survey said

600, not 3000 running rampant. He ended, "I join Asemblyman

Dunlap in asking for an Aye vote on this important bill."

Because Zberg mentioned numbers again, it gave me a good

lead into my final statement--on the spot I remembered an

additional fact about lions and their populations, and I began

my statement with it--

"One of the reasons we are so concerned with there only

being 600 mountain lions is that we're not dealing with

animals that proliferate as quickly as bunny rabbits or house

cats--ordinarily a female lion has one or two cubs every two

years. Contrary to suggestions from the gentleman from

Buttonwillow, the purpose of this legislation is solely to

protect the California Mountain Lion-the fate of the bobcat,

coyote, and rattlesnake can be judged by this legislature on

their own merits, if and when anyone chooses to introduce

bills to protect them. But I won't be the one." I might've

added that I wasn't about to hold a press conference flanked

by two rattlesnakes.

I figured the Republican's citing of the united

opposition and the UC professor's opinion had lost me a few

votes, so I turned directly to him as I continued--

"It's true that the agricultural lobbies are against this

bill--but how many individual farmers have each of you heard

from? I have only one letter from a farmer opposed to this

bill--the farmers in my district are much more concerned about

pesticide control and labor laws than the fate of the mountain

lion. I suggest to you that farmers know their interests

better than their lobbyists--and they know an old crippled

lion isn't going to kill enough sheep to raise the price of

lamb, particularly before a permit can be issued to legally

kill it. I also suggest to you that farmers know that mountain

lions provide a function--holding down damage to crops from

deer and raccoons."

The main farming activity in Napa County was winegrape

growing. Since raccoons have been known to damage grapevines,

growers and vintners were not opposed to my bill. I also

shared with them a desire to keep the environmental integrity

of the Napa Valley intact. Some of them were born and raised

in the valley and were genuinely and sentimentally attached to

its preservation. Others knew darn well they had to preserve

the land, water, and air in order to grow grapes...but we

didn't always agree. I urged public hiking trails rimming the

valley and up and down the banks of the Napa River. Growers

and vintners saw this as an infringement on private property--

mostly theirs. They were however willing to sacrifice the land

for wineries and visitor parking lots along with increased

traffic. All of my environmental bills weren't as dramatic as

the Mountain Lion bill. I had many to preserve open space and

protect agriculture from excessive property taxes. This was

part of preserving the valley.

Concluding my closing statement I said, "Universty of

California Professor Starker Leopold did say that AB 660 is

unnecessary. However, his conclusion wasn't based on his

factual and scientific information (which, incidentally, backs

up our basic information justifying this bill--a small number

of lions, diminishing; a reduced natural habitat.) The

professor said specifically that we didn't need this bill

because the Fish and Game Commission presently has the author-

ity to impose limits and restrict killing. His conclusion was

based on his misplaced confidence that they'd do their job as

they're supposed to--the Fish and Game Commission are

political appointees mostly representing hunting interests and

they believe that wild animals are there, basically, for one

reason--to be hunted. The professor's conclusion that AB 660

is 'unnecessary' was a political judgement, not a scientific

one. I believe this legislature is best suited to make its own

political judgements. We don't need no college professor to

tell us our business"

I'd intended to end debate with a repetition of my

'conservation maxim', When in Doubt, Preserve--but as I

watched the reaction to my statement on the professor, I could

see that I'd hit home, so I cut it short with a minute of time

left over, saying, "I ask for an Aye vote on this bill to

protect the California Mountain Lion." I held my hand on the

voting switch as I sat down so I could flip it to green as

soon as the roll opened. Psychologically it's good to get as

many green lights up on the board as soon as possible.

Legislators are all supposed to be great leaders making

independent judgements, but sometimes they act more like sheep

and go running after whoever moves first. Eight or ten early

green lights usually bring on more.

Debate on some bills is as abbreviated as thirty seconds,

others may last fifteen or twenty minutes. This one took

fifteen. The longest debate on any bill that I carried was

Senate Bill #1, during the first extraordinary session of

1975. It was the Ag-Labor Relations Act, sponsored by Governor

Brown. Debate lasted over an hour. Once in a while a major tax

bill might take a full morning, afternoon, or evening session.

The initial vote on the Mountain Lion bill was 37 Aye, 12

No. This was a 3-1 majority--of those voting. An absolute

majority of the whole Assembly, 41 out of 80 possible votes,

is required to pass a bill. So far only 49 legislators had

voted. The rest were either not present, had not been paying

attention to the vote, or had deliberately not voted. I stood,

and moved for what's known as a 'call of the house', which

means a postponement of final action on the bill until more

assemblymen showed up and got their votes in. While the next

order of business on file came up, I went to the clerical

staff under the Speaker's rostrum and asked for a record of

the vote. They gave me a card with the names of all of us in

alphabetical order, and after each name an Aye and a No

column, marked by computer to show how or if we'd voted.

I found the names of a few who hadn't, who I thought were

probably favorable to the bill, and set out to track them

down--in their offices or at the perimeters of the chambers or

wherever they were--meanwhile, the legislative process went on

like a five ring circus, presentation of bills, voting, and

buttonholing, all going on at once.

I can remember having two or three bills under call at one

time--other members, at this same moment, could be in the same

boat. So what you have is a dozen legislators walking around

with bills up in the air, pulling cards and pencils out of

their pockets, figuring how many votes they need to land them-

-accosting each other, sometimes smiling and saying thanks,

sometimes having heated private arguments. It must look

strange to someone seeing it for the first time. Probably the

impression would be one of chaos and rudeness. A real circus

fan--a reporter or lobbyist, a professional capitol spectator,

that is--sees what's going on in a corner of the tent. While

the ringmaster calls his attention to the center, where Miss

Fifi rides an elephant on tiptoe, or a legislator is making a

speech, the fan notes 'oh there's Dunlap, he's got that bill

on the mountain lion, and there comes so-and-so, he's in from

L.A., and Dunlap's talking to him, I can see from the way he

nods he's got another vote now he's going over to Blank, yeah

he's got another vote lined up there too--looks like Dunlap's

got his votes but he's continuing to hit people up, probably

wants to nail it down for sure.

I was getting enough votes. I had 45 promised when, as

business on one bill was completed, I threw up my mike and

said, "Mr. Speaker, I'd like to remove the call on item 22."

He went through his verbal mumbo jumbo; the call was removed

and the names of absentees were announced one at a time by the

clerk--at which point they voted orally, and their votes were

recorded. The vote stood at 52--14, and I was about to ask

that it be 'announced', when three members asked to change

their votes from No to Aye, making the final vote 55--11.

These last three switch voters wanted, in the record of the

final vote, to be in with the majority. By originally opposing

the bill, they'd shown their farmers and cattlemen (lobbyists

for whom were sitting in the gallery behind the chambers) that

if there'd been a chance to defeat it they'd have done their

part. Now they figured they might as well cut their losses

and go with the winner.

Voting on the floor of the Assembly is an electric

event--like watching the electronic scoreboard in the closing

seconds of an extremely close basketball game--all the points

are 'scored' in a matter of seconds and the game's over--but

on the floor of the Assembly there's another bill and another

game's going on right away. Sometimes the continuous tension

results in legislators playing games with the legislative

process--a member might say in the middle of his bill

presentation, "All right, Mr. Speaker, I would like my

colleagues to know that this bill isn't any good and I think

everybody ought to have a choclate ice cream cone right now."

The presiding officer might answer, "Thank you, Mr.

DeStefano for your recommendation, will the sergeant-at-arms

please retire and bring in 80 cones, 40 vanilla, 39 choclate,

and one spumoni for Mr. DeStefano."

Or, a legislator might finish a short speech on what he

thinks is a non-controversial bill--he sits down, asking for

an Aye vote and flicking his switch to green--as he looks up

at the scoreboard his vote is the only green in a sea of red

lights. He turns and frantically looks around the floor at his

colleagues--seeing a smile on one or two faces, he realizes he

has been made the object of a conspiracy--and relaxes a

little--looking back at the board he sees the red lights

gradually turning to green and he smiles too. After everyone

has had a good jolly old laugh, business gets underway again.

The split second the vote was finally announced on the

Mountain Lion Bill, I had a feeling of exultation--like 'this

calls for two drinks before lunch!!!'--but it didn't last.

There was no time to feel and damn little for introspection--I

just jumped back on the treadmill (it's running and you're on

it and there isn't time to get off and think about it) and I

made a beeline for the floor telephone. You can call

practically anywhere in the world from the floor of the

assembly for nothing (that is, you don't pay for it), but I

was just calling upstairs to my office. Wanda answered and I

said, "The bill's in 55-11--wire service will cover the

dailies; let's take credit with the district weeklies, get out

a press release for them and tell Gage he can relax." Mike was

already on the phone and he broke in saying, "I already heard

the results on the squawk box" (Assembly proceedings are

broadcast to receivers in the Speaker's office and several

other locations in the Capitol building) "don't waste time

congratulating yourself; call our friends on Senate Rules

right away and get the bill assigned to Natural Resources and

Wildlife. It'll die if they send it to Ag."

I whined my reply, "You had to think of that--do I really

have to?" He was right but I'd have preferred to relax a

moment or two.

Mission accomplished, I turned to thoughts of my little

gray home in the west--it's a corner of heaven itself. There

are two eyes that shine because they are mine, and a thousand

things other than this. Calling home I told Janet of my

success and she shared my exultation.

"Hey, Sox, I'm on the floor the Mountain Lion Bill just

went through 55-11."

"Wow, Great!"

"Yeah, I'm pleased. How are you?"

"Just fine. Can you come home early and celebrate?"

I couldn't. It'd be 8 p.m. before I got home. Alan and I

had the tax bill and I had to stop in Fairfield. "Maybe we can

do something special this weeked," I told her, but of course

that'd depend on what was happening when the weekend arrived.

It was nice to talk to Janet but I also felt guilty--she and

the kids did tend to play second fiddle. The job came first

more often than not.

Before going to lunch I ran into Jess Unruh in the men's

room. Jess at this time was minority leader--the Democrats

having lost control of the assembly, Republicans held

Speakership and all key committee chairmanships.

Unruh knew that Sieroty and I had our tax bill up in

committee that afternoon--before we started to talk about it

Jess said, "shhhhhh" and looked under all of the stalls to

make sure we were alone. He then said, "You're fighting a

loser, but I might be able to get you a vote or two. A couple

of guys on the committee owe me, from when I was Speaker. They

might vote for the bill knowing it's gonna get killed in Ways

and Means anyway."

"We'd appreciate any help you can give us, Jess."

"I'm not doing this just to help you, I want to use your

bill, John." It was 1970 and Jess was running for Governor

against Reagan. He needed to have concrete examples of tax

reform as part of his campaign.

That fall, Jess did mention the Dunlap-Sieroty bill as he

was campaigning against Reagan, and he did well to expose

Reagan as the candidate of the very wealthy--the tax bill

helped him do this. Some of the bloom had worn off Reagan's

image but he was still a very popular governor. Jess couldn't

crack Reagan's popularity and he didn't inspire people

himself.

The great Democrats have been those that inspire. I

believe the great message of the Democratic Party is

innovation and change, which are threatening to people, and

you can't come off successfully with this unless you're also

bringing a message of hope and inspiration--and mostly all

Jess did was Negative Reagan. He did a pretty good job of this

but he didn't inspire enough people to believe in his own

candidacy. Jess lost by half a million votes, a decisive

defeat, with the only consolation being that it was half the

margin Reagan had beaten Pat Brown by 4 years earlier.

Once John and I tossed large ashtrays to each other at

the same time, and the two ashtrays hit in mid-air, showering

glass all over. We were greatly surprised. Ruth Siegle, one of

my district representatives, once gave me a metal horn with a

rubber squeeze ball on the end of it--sort of a Harpo Marx

device. At times of frustration and bedevilment I used to blow

it--sometimes into the telephone.

Edna Brown joined my staff after working a year and a

half free as an intern. She was a great lady.

By 9:30 both interns and my second secretary had arri-

ved on the scene. The first intern had been dispatched for

coffee. Somehow we all managed to touch base, say hello, and

get on with the various things we were doing in between

phonecalls, reading memos, and opening the day's mail.

When I left the office to go to the legislative chambers

a little after ten, Wanda gave me a folder with legitimate

mail in it, junk having been sorted out. I might have time to

read it during dull moments on the floor.

Session was supposed to start at ten sharp, but never

really got underway until about 10:30. This demonstrated yet

another 'pair of opposites', the Virtue of Promptness but the

Sagacity of Tardiness. You waste time by being on time,

because others generally aren't. Today I was prompt because,

as I'd promised Gage, I needed to try to line up at least a

few votes before debate. I hadn't done a detailed job of

getting advance commitment. The opposition came from limited

quarters. We seemed to have a popular thing going.

The back entrance to the Assembly Chambers (For

Legislators Only) is a narrow hallway within which the

members' elevator stops. Coming out of the elevator I walked

quickly past the Sergeant-at-Arms, saying hello almost over my

shoulder. Anyone who wasn't a member would've been stopped at

that pont. Entering the chamber I walked under the Speaker's

rostrum and 80 feet across the floor to my desk, noticing a

couple of other early arrivals on my way. After putting down

my files I made a beeline for my former seatmate, Ernie

Mobley. I told Ernie my Mountain Lion Bill was coming up today

and I hoped I could count on his vote. He told me that his

farmers and cattlemen didn't like the bill. "It just concerns

sports shooting," I told him, "livestock is still protected."

He said he'd listen to the debate and make up his mind. I had

similar conversations with eight or ten others, catching them

near the door as they trickled in. Some, I asked for their

vote out and out. "Are you familiar with AB 660, my Mountain

Lion bill?" etc. Others, I knew what their hesitations might

be so that's where I started out talking. At least half of

those I talked to were favorable about the bill.

Just a little before a quorum arrived on the floor I went

to the coffee room in the back of the Assembly Chamber to sip

coffee and see if I could pick up a couple more votes. Willie

Brown was in a corner talking to a member of his staff. I

mentioned the bill to him briefly but already knew I had his

support on it. Willie had a copy of the little book Jonathan

Livingston Seagull in his hand. He said he was intrigued with

its message. "Birds and man have no limits", he said.

Coffee and donuts are provided in this rear chamber for

legislators and their guests. A P.A. system relays the

activities of the house, so you can talk to peole, hear what's

going on out on the floor, and drink coffee at the same time.

It's a formality that's persisted, that food and beverage

aren't allowed out on the floor. From the coffee room you can

be back on the floor in a matter of seconds, voting or in the

middle of debate...I got up, leaving my half empty coffee cup,

and started to walk toward the swinging door into the chamber.

Before I reached it, it opened and my good friend Assemblyman

Alan Sieroty came in. He smiled as if he was actually glad to

see me and said, "I was lookng for you--my staff tells me

you're going to take up your Mountain Lion bill today--

anything I can do to help?"

"I was going to ask you if you would--just listen to

debate and jump in if you think I'm in trouble. You know the

bill."

"Sure. It's a good bill. I wish I had a bill with a real

live animal in it."

"Your paleontologist friends couldn't provide you with

one, could they?" I said. Alan had recently, on request of

some friends of his from academia, put in a bill to designate

Smiladon Californicus (the California Sabretooth Tiger) the

'Official State Fossil'.

"No," Alan responded, "but I sure would've liked to bring

one up here for debate."

"Do you think it'd fit in the elevator?"

"I think so. I don't think they're that big."

"I can see it--on the way up from the basement you and

Curly" (the elevator operator) "each holding a tusk."

Most legislators are so embroiled in their own bills that

they don't have time to think of volunteering to help somebody

else. Alan had a lot of his own going on but he often knew of

my important bills, because we shared interests. And, we were

just darn good friends.

At 10:30 a quorum (majority of the members) having

appeared, the House was called to order and we started taking

up the day's business item by item in the order designated in

the pamphlet (daily file) on our desks. While the Speaker (or

his designated helper) went through routine matters in a

perfunctory mumbo-jumbo manner, I sat half-listening but going

through the material in the Mountain Lion file to prepare my

opening statement. I already knew the material A to Z--I just

had to make a couple decisions about where to begin my speech.

Assembly rules provide that the bill's author has an

opening and a closing statement, a maximum of five minutes for

each. Other speakers are similarly limited. The presence of

active opposition meant to me I should give the bill full

treatment. Others following in debate are recognized to speak

in the order in which they raise up their microphones--the

mikes are mounted on flexible metal arms and can be stuck up

in plain sight...sort of like a kid raising his hand in

school.

At 10:55 we reached item 22 on the Daily File. The Clerk

read the bill number, AB 660. I raised my mike and the Speaker

recognized me, saying, "Mr. Dunlap, are you ready to proceed?"

I answered, "Yes, Mr. Speaker," and looking around saw two

other members raise their mikes--the opposition was prepared,

not lying in the weeds or forgetting their job.

I began my speech.

"Members--in 1923, a year after I was born, there were

two passenger pigeons in the whole world--both were males.

Rather obviously, there aren't any passenger pigeons now. We

have now about forty California Condors alive,* and their

________________

*Since then the number went down to about a dozen and

Zoologists have now started capturing eggs and raising baby

Condors in captivity, with the idea of replanting them in the

wilds. Their number now is again in the forties.

number has been diminishing. Maybe they'll survive and maybe

they won't...Too many times, we've recognized that a species

is endangered--too late. This hasn't just happened, we made it

happen." I went on with the guilt approach, not just to try to

make them feel miserable, but to get them to recognize that

the Mountain Lion Bill gave us a chance to do the right

thing, start turning around and taking responsibility for our

actions.

I continued, "The State used to pay people to shoot

mountain lions--this bill is the next logical step after

removal of the bounty--the opposition may have said things to

you about the bill, but what it really does is quite simple.

It prohibits sport shooting of the California Mountain Lion.

That's all. No more no less. AB 660 has the support of all

major conservation organizations including the Audubon Society

and the Sierra Club--also, the Vallejo Rod and Gun Club, and

the Mountain Lion Coalition."

Gage and I were in on the formation of the Mountain Lion

Coalition, along with several wildlife preservationists and

scientists. The group was formed to help enlist support and

develop publicity. At one strategy session a coalition member

brought tame mountain lions with him. Mike, attending for me,

had a brainstorm and asked if the lions could be used at a

press conference, to give the bill a good sendoff. The owner

consented, but when Mike told me about it I was at first very

negative. It seemed like unnecessary grandstanding.

Mike said, "You know darn well it'll help the bill--it'll help make

people less afraid of lions and it'll increase the number of

people that read about your press conference by 5,000 percent.

Drop your false modesty, John." Mike kept on arguing, and I

finally gave in, partly to him and partly to my ego, which

said 'Go Man Go.' I said to myself, 'I can use the press

conference to emphasize the importance of the bill as a symbol

of the need for conservation of all wildlife'--this satisfied

my image of myself as 'a thoughtul person who doesn't just go

off grandstanding'.

The lions arrived at the Capitol through the members'

entrance in the underground garage and were taken out of the

car in their cage, which was wheeled over to the Assembly

members' elevator, which took them to the first floor. Curly

for years after that used to refer to me as 'the man with the

cats'. They were taken to a small room between the governor's

office and the press conference room. This is where I met

them, about thirty seconds before the conference started. I

hadn't thought to be apprehensive, but I became so instantly

when I went in there and first saw them. They were big, bigger

tha St. Bernards and a lot more agile, and they were moving

around out of the cage. I was glad to see the owner had them

on leash. I was only a little scared. I said, "Well, it's time

to get started, will you bring them in?" And we went into the

press conference room.

The owner brought the lions up and stationed them one on

each side of me at the conference room table. Before I even

sat down the TV cameras started to click and spin. I smiled

out at them, as if to say, "My lions and I have got a great

bill; we want you to listen and help tell our story to the

world." I launched into my presentation, introducing the lions

and the bill. I pretty well lost myself in the show, and

responding to questions afterward--except once when the lion

to my left was moving around and straining at his collar. I

patted his front paw to try to quiet the beast, and it

responded with halfway between a snarl and a roar and reared

its head. I felt uneasy, bordering a little on panic. What the

hell do I do now?--it wouldn't look good if I left--not at

all--but the owner calmed it down right away--later, he told

me its paws were sensitive because they'd been surgically

declawed.

Once John and I tossed large ashtrays to each other at

the same time, and the two ashtrays hit in mid-air, showering

glass all over. We were greatly surprised. Ruth Siegle, one of

my district representatives, once gave me a metal horn with a

rubber squeeze ball on the end of it--sort of a Harpo Marx

device. At times of frustration and bedevilment I used to blow

it--sometimes into the telephone.

Edna Brown joined my staff after working a year and a

half free as an intern. She was a great lady.

By 9:30 both interns and my second secretary had arri-

ved on the scene. The first intern had been dispatched for

coffee. Somehow we all managed to touch base, say hello, and

get on with the various things we were doing in between

phonecalls, reading memos, and opening the day's mail.

When I left the office to go to the legislative chambers

a little after ten, Wanda gave me a folder with legitimate

mail in it, junk having been sorted out. I might have time to

read it during dull moments on the floor.

Session was supposed to start at ten sharp, but never

really got underway until about 10:30. This demonstrated yet

another 'pair of opposites', the Virtue of Promptness but the

Sagacity of Tardiness. You waste time by being on time,

because others generally aren't. Today I was prompt because,

as I'd promised Gage, I needed to try to line up at least a

few votes before debate. I hadn't done a detailed job of

getting advance commitment. The opposition came from limited

quarters. We seemed to have a popular thing going.

The back entrance to the Assembly Chambers (For

Legislators Only) is a narrow hallway within which the

members' elevator stops. Coming out of the elevator I walked

quickly past the Sergeant-at-Arms, saying hello almost over my

shoulder. Anyone who wasn't a member would've been stopped at

that pont. Entering the chamber I walked under the Speaker's

rostrum and 80 feet across the floor to my desk, noticing a

couple of other early arrivals on my way. After putting down

my files I made a beeline for my former seatmate, Ernie

Mobley. I told Ernie my Mountain Lion Bill was coming up today

and I hoped I could count on his vote. He told me that his

farmers and cattlemen didn't like the bill. "It just concerns

sports shooting," I told him, "livestock is still protected."

He said he'd listen to the debate and make up his mind. I had

similar conversations with eight or ten others, catching them

near the door as they trickled in. Some, I asked for their

vote out and out. "Are you familiar with AB 660, my Mountain

Lion bill?" etc. Others, I knew what their hesitations might

be so that's where I started out talking. At least half of

those I talked to were favorable about the bill.

Just a little before a quorum arrived on the floor I went

to the coffee room in the back of the Assembly Chamber to sip

coffee and see if I could pick up a couple more votes. Willie

Brown was in a corner talking to a member of his staff. I

mentioned the bill to him briefly but already knew I had his

support on it. Willie had a copy of the little book Jonathan

Livingston Seagull in his hand. He said he was intrigued with

its message. "Birds and man have no limits", he said.

Coffee and donuts are provided in this rear chamber for

legislators and their guests. A P.A. system relays the

activities of the house, so you can talk to peole, hear what's

going on out on the floor, and drink coffee at the same time.

It's a formality that's persisted, that food and beverage

aren't allowed out on the floor. From the coffee room you can

be back on the floor in a matter of seconds, voting or in the

middle of debate...I got up, leaving my half empty coffee cup,

and started to walk toward the swinging door into the chamber.

Before I reached it, it opened and my good friend Assemblyman

Alan Sieroty came in. He smiled as if he was actually glad to

see me and said, "I was lookng for you--my staff tells me

you're going to take up your Mountain Lion bill today--

anything I can do to help?"

"I was going to ask you if you would--just listen to

debate and jump in if you think I'm in trouble. You know the

bill."

"Sure. It's a good bill. I wish I had a bill with a real

live animal in it."

"Your paleontologist friends couldn't provide you with

one, could they?" I said. Alan had recently, on request of

some friends of his from academia, put in a bill to designate

Smiladon Californicus (the California Sabretooth Tiger) the

'Official State Fossil'.

"No," Alan responded, "but I sure would've liked to bring

one up here for debate."

"Do you think it'd fit in the elevator?"

"I think so. I don't think they're that big."

"I can see it--on the way up from the basement you and

Curly" (the elevator operator) "each holding a tusk."

Most legislators are so embroiled in their own bills that

they don't have time to think of volunteering to help somebody

else. Alan had a lot of his own going on but he often knew of

my important bills, because we shared interests. And, we were

just darn good friends.

At 10:30 a quorum (majority of the members) having

appeared, the House was called to order and we started taking

up the day's business item by item in the order designated in

the pamphlet (daily file) on our desks. While the Speaker (or

his designated helper) went through routine matters in a

perfunctory mumbo-jumbo manner, I sat half-listening but going

through the material in the Mountain Lion file to prepare my

opening statement. I already knew the material A to Z--I just

had to make a couple decisions about where to begin my speech.

Assembly rules provide that the bill's author has an

opening and a closing statement, a maximum of five minutes for

each. Other speakers are similarly limited. The presence of

active opposition meant to me I should give the bill full

treatment. Others following in debate are recognized to speak

in the order in which they raise up their microphones--the

mikes are mounted on flexible metal arms and can be stuck up

in plain sight...sort of like a kid raising his hand in

school.

At 10:55 we reached item 22 on the Daily File. The Clerk

read the bill number, AB 660. I raised my mike and the Speaker

recognized me, saying, "Mr. Dunlap, are you ready to proceed?"

I answered, "Yes, Mr. Speaker," and looking around saw two

other members raise their mikes--the opposition was prepared,

not lying in the weeds or forgetting their job.

I began my speech.

"Members--in 1923, a year after I was born, there were

two passenger pigeons in the whole world--both were males.

Rather obviously, there aren't any passenger pigeons now. We

have now about forty California Condors alive,* and their

________________

*Since then the number went down to about a dozen and

Zoologists have now started capturing eggs and raising baby

Condors in captivity, with the idea of replanting them in the

wilds. Their number now is again in the forties.

number has been diminishing. Maybe they'll survive and maybe

they won't...Too many times, we've recognized that a species

is endangered--too late. This hasn't just happened, we made it

happen." I went on with the guilt approach, not just to try to

make them feel miserable, but to get them to recognize that

the Mountain Lion Bill gave us a chance to do the right

thing, start turning around and taking responsibility for our

actions.

I continued, "The State used to pay people to shoot

mountain lions--this bill is the next logical step after

removal of the bounty--the opposition may have said things to